I built an AI agent to respond to student discussion board posts...

... but I'm too afraid to use it.

This is the story of how I built my own AI bot that is capable of reading and responding to students in my online discussion boards. I hope this story illustrates the promise and peril of the emerging technology known as “AI agents” as well as the importance of human supervision in future AI-powered automation in education.

What is an AI agent?

“AI agents” are the latest innovation from the leading AI labs. They are autonomous bots that are capable of carrying out tasks over several minutes, interacting with the world on your behalf via the web.

The latest multimodal models (like GPT-4o) can generate text and media as well as perform basic web searches. But those models can’t go online and order you a pizza.

An AI agent, on the other hand, CAN order you a pizza (or complete any other web-based task). To carry out its assigned task, the AI agent opens a web browser on a remote virtual machine. It then captures screen shots from this browser and feeds the images into an advanced AI model. The model then decides where to click and what to type in order to complete the task.

AI Agent (noun): An advanced artificial intelligence that is capable of ordering a pizza.

A demonstration of an AI agent’s capabilities

ChatGPT Pro subscribers have access to a prototype AI agent called “Operator.” Let me show you how it works with a simple demo. One of the first things I asked Operator to do for me was create a funny meme of Hugh Jackman.

After entering the prompt, I just watched the AI agent work. It created a plan of action, searched for a Hugh Jackman photo, and used an online meme generator to create a (honestly kind of funny) meme. The entire process required no human intervention. (Well, almost no human intervention - more on that in a moment.)

Operator creates time-lapse videos of its actions, so you can view a condensed video of Operator’s work here or in the animated gif below. If you watch the video closely, you will notice that Operator struggles in the middle of the task.

Did you see the struggle? In addition to several mis-clicks along the way, Operator spent 2.5 minutes (over 60% of the entire operating time) just trying to locate the image that it downloaded.

These kinds of errors are forgivable for a beta version of this new technology. In the near future (when these basic computer navigation issues are fully resolved), this entire task would have taken about 20-30 seconds. Surely, this is going to be quite revolutionary (at least in the meme-creating industry).

Sidebar: I think it is fascinating that the AI agents haven’t fully learned how to navigate computers yet. It reminds me of the early 1990’s when my mom got her first computer. I sat by my mother’s side showing her how to find her downloads folder as she asked me if it was ok to click OK. Ah yes, fond memories…

“Andrew! How do I find my downloads?”

- My mom (and Operator, apparently)

Current AI agents still depend on humans…

As of right now (April 2025), AI agents are kind of like nervous interns. They are so afraid of making a mistake that they ask way too many questions. In order to make Operator usable, I find that I have to specifically request it to stop asking me so many darn questions. More than any other question, Operator loves to ask “Should I proceed?”

At first I thought Operator’s overcautious nature was a bug, but after constructing my own AI agent, I’m think that these frequent pauses are an important design feature (and integral to the safe operation of an AI-powered autonomous agent.)

As AI agents continue to improve over the coming months, it is reasonable to expect that they will get faster and better at interacting with the web, eventually becoming legitimate virtual assistants who can help us automate portions of our workday.

“But what about NOW?

I want a competent AI agent NOW!”

-Andrew Vanden Heuvel

Building my own AI agent

As an online professor, I find responding to student comments in online discussion boards to be one of the more mundane parts of my job. So writing (or at least drafting) replies to student discussions is one of the first tasks that I would like to outsource to AI.

I’m not a software engineer, but I do like playing around with code, so I set out to Frankenstein my own simple AI agent using APIs (visible in the cartoon below as green squiggly lines).

For the purpose of this article, here’s all you need to know about APIs: nearly all of the websites you interact with contain a hidden back-end that allows programs to send “requests” that can emulate human activity.

Do you want to subscribe to a YouTube channel? An API call can do that.

Do you want to download a user’s latest Instagram post? An API call can do that.

Do you want ChatGPT to write a poem for you? An API call can do that.

Do you want to respond to a student’s discussion post in Canvas? An API call can do that.

Whereas Operator can “see” websites and “click” on links, my AI agent will use APIs to interact with websites. This is much easier to create, but less versatile. While my agent will still have an AI-powered brain, it will only be able to complete one type of task: reading and replying to student discussion posts.

Note: Much of my experimental work uses Google Apps Script to create automations between Canvas, Google Drive, and OpenAI, but the same techniques could be applied to any other platforms with robust APIs.

Ok, here’s the plan…

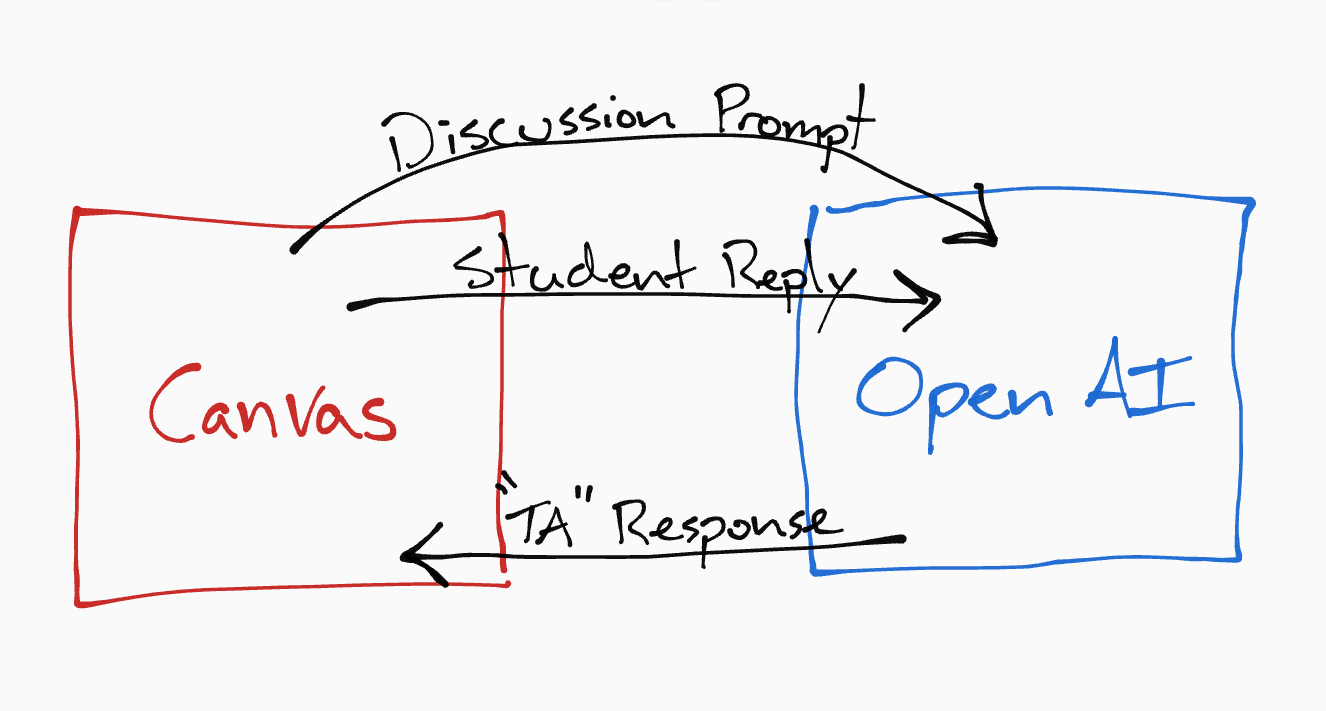

Using API calls, I will read the initial discussion prompt and student posts from my online class in Canvas. I will send that to OpenAI along with some general instructions like “You’re an astronomy professor.” The AI model will generate a suitable “teacher response.” Finally, that response will be sent back to Canvas where it will be published as a reply to the student’s original post.

Here’s a diagram showing the basic strategy for creating my AI agent. Each of the black arrows represents an API call.

There’s just one problem… implementing this plan would be downright dangerous.

That may sound like hyperbole, but without several additional safeguards, I may run the risk of violating student data privacy laws, making factual errors, violating academic integrity policies, or (gulp) inadvertently posting something cringey to my students.

I have to find a way to add these essential safety features:

Protecting student data - Any information sent to OpenAI must be completely deidentified and anonymous.

Human verification - All AI-generated replies must be read, edited, and approved by me before being published.

Disclosure - Students must be informed that generative AI is being used to draft my responses.

Revising the plan

Let’s take these concerns in reverse order. If I were to implement this tool, then the disclosure should probably be included in both the course syllabus and the discussion prompts themselves. No problem - that is easy to add. Although I am curious how students would respond to such a disclosure...

“AI Disclosure: Throughout our course, I may use generative AI to assist in drafting replies to your messages and discussion board posts. If that makes you uncomfortable, let me know.”

Human verification and protecting student data can both be addressed by a single clever solution - using Google Sheets as an intermediary between Canvas and OpenAI. Check out the drawing below to see what I mean.

The discussion prompt and student replies from Canvas are passed via API into Google Sheets. The data is then automatically deidentified, removing student names and userIDs. Only then is the discussion data passed along to OpenAI where a draft reply is generated and returned back to the same Google Sheet. From there, I can edit (or entirely rewrite) my responses before pushing them back out to the Canvas discussion board.

This gives me total control over what data is shared and what responses are posted to the online discussion board. That feels safe.

Sidebar: Notice that my AI agent requires human intervention for safety reasons. I strongly suspect that OpenAI’s Operator asks for regular human intervention (all those annoying questions) for the same reason - safety. While AI optimists predict that autonomous AI agents will soon be capable of working hours or days on complex tasks without human intervention, I wonder if that will ever be safe.

How did I actually build this thing?

The first thing I did was enable the APIs in my Canvas, OpenAI, and Google Drive accounts. I then used ChatGPT to help me create a series of functions that perform the relevant API calls, reading and writing data back and forth.

When I call on the AI model to draft a teacher response, I include a detailed system prompt that outlines my requirements. Here’s just a portion of it:

You are a friendly and approachable astronomy professor engaging with students in an online discussion board. Acknowledge their contributions, and gently guide them towards a deeper understanding. Keep the conversation focused on the questions raised in the discussion prompt, and keep the tone warm, light-hearted, and authentic. Do not use exclamation points. Also, avoid using the words 'dive' or 'delve' - you say those too much.

The AI agent lives in Google Sheets and runs in four distinct phases with a manual trigger between each step.

Step 1 - Read the latest discussion posts from Canvas and write them to Google Sheets with deidentified meta data.

Step 2 - Use AI to generate a draft instructor response to each student discussion post and record the result in the Google Sheet.

Step 3 - [Human intervention] Manually edit and approve the instructor response.

Step 4 - Push the approved instructor responses back to Canvas and mark the items submitted.

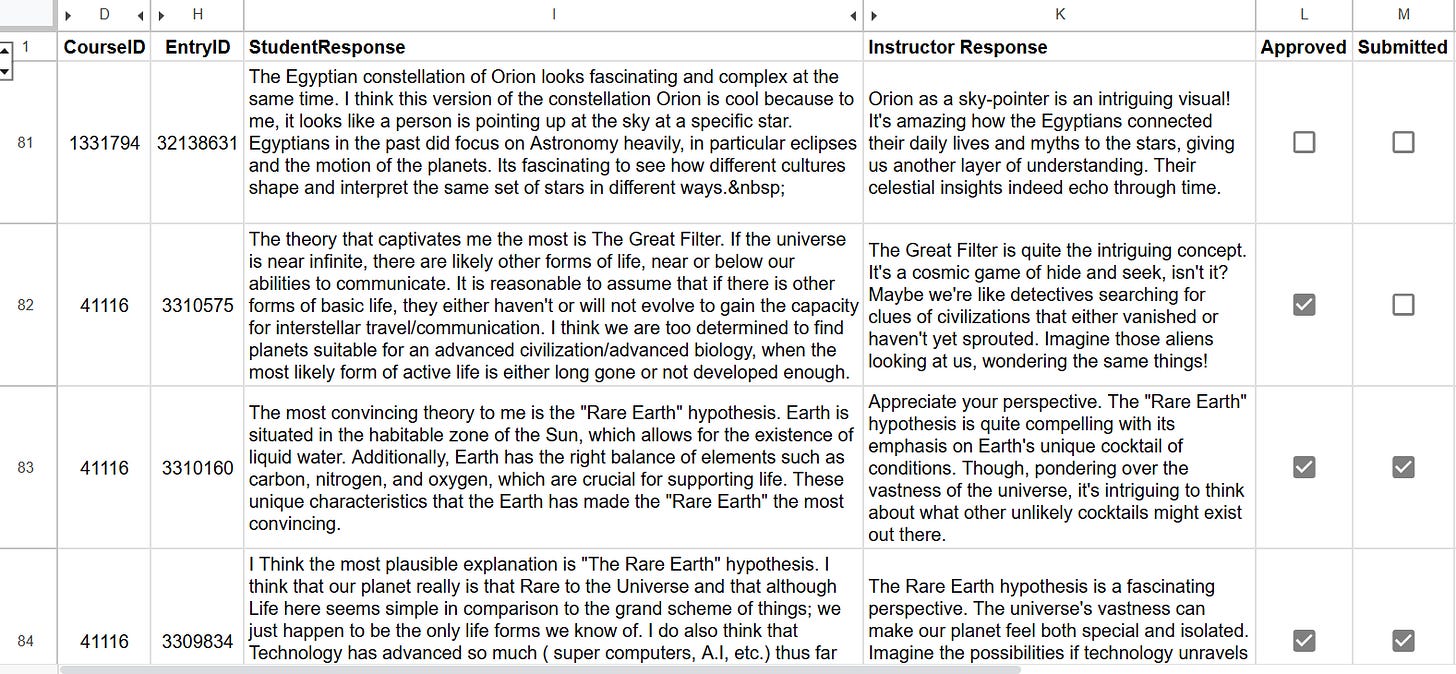

Here’s what the AI agent actually looks like.

ChatGPT does a great job drafting replies to the students - often adding humorous and light-heated comments (just as I requested). I can further edit these responses directly in the spreadsheet. And then I simply check the “Approved” box when I am ready to publish.

The trouble is… I’m too afraid to use it.

I tested the agent thoroughly using a sandbox course to make sure that everything is working properly (and it does!), but I still can’t bring myself to actually use it in a live course with students.

The truth is that I am afraid and ashamed to use an AI system to interact with students. I don’t think I fully understand why I feel that way (perhaps it is worth exploring more in the future), but here are some of my unfiltered concerns:

I’m afraid that students will be able to tell that I used AI assistance and that they will view this as cheating (or some kind of laziness).

I’m afraid a disgruntled student could try to publicly shame or embarrass me for using AI in class.

I’m afraid that my employer will view this as a violation of some law or policy and fire me.

I don’t know - what do you think? Are any of these fears justified? Is there anything shameful about building a robust AI teaching assistant and deploying it in class?

A positive vision for using AI agents in online discussions

I had tons of fun making my little AI agent, and I think it actually is a really useful tool - primarily because it can enhance the student experience in an online class.

From my vantage point, the real value of this AI agent is not that it can help me spend less time responding to discussion posts, but rather that it can help me respond to more students (potentially all of my students) in the same amount of time as before.

Interaction in discussion boards is an essential component of establishing teacher presence in an online course. AI agents like the one I created can act as force multipliers, helping instructors promote more discussion and interaction, leading to an online course that feels more fully alive and interactive.

To learn more about the author or to contact him, visit AndrewVH.com.